From old outlaws to new icons: Ben Knight on his thwarted acting career, and the transformations in Berlin’s theatre life ever since he left it. (Published in Exberliner, July 2022)

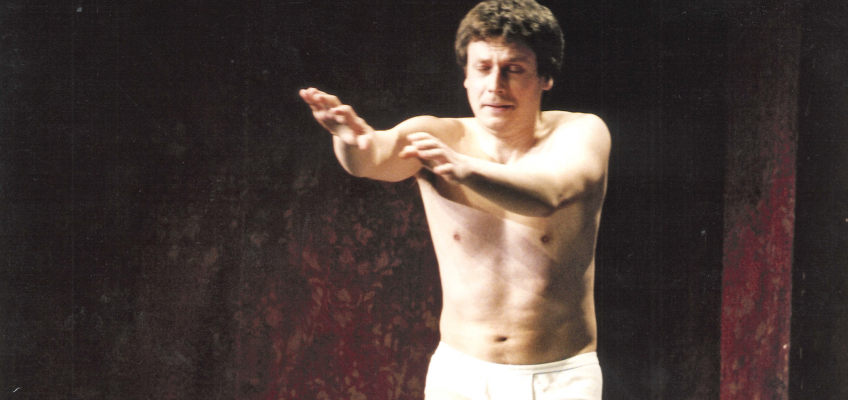

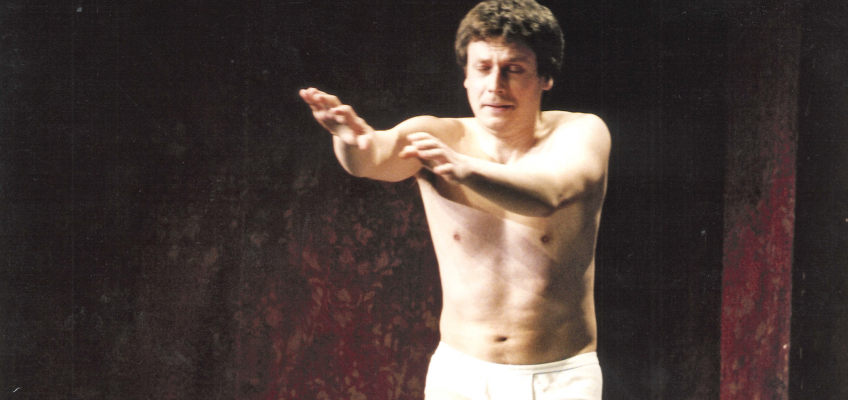

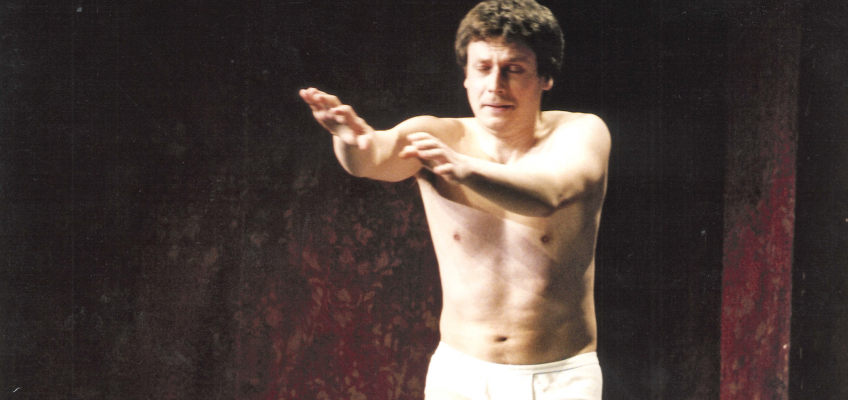

(Photo: Thomas Grünholz)

You can leave your hat on

My character was called Jay, and he had four lines, the third of which I enjoyed saying, because it was the one that made the audience stop laughing. Up to that scene, the audience was usually already laughing a lot. This was my first appearance on a professional stage, and it was the biggest hit I would ever be involved in. Ladies Night was a version of the British movie The Full Monty, and in this production five German men played unemployed northern English steelworkers who stripped to groovy 1970s songs, in between scenes depicting male awkwardness, desperation, and despair, and finally triumph. The more clothes these men took off, the more they triumphed, until at the very end they took all their clothes off (police uniforms in this case) and the lights went out just at the moment you were about to see their cocks. Then the play was over. By then, our audiences had often become like the audiences at actual male strip shows. On some Friday nights, the 300-seat auditorium was filled with gales of female hilarity so relentless the actors could barely find a moment to get their lines out.

And in this howling din, towards the end of the slightly calmer first act, my character achieved a moment’s silence with his third line. Jay was auditioning to be a stripper, and he’d realized, as Serge Gainsbourg’s “Je t’aime” started, that he wasn’t cut out for this. When he did finally pull his trousers down, revealing a big pair of y-fronts (easy laugh there), he broke down in humiliation. (Not being an actor, I played this by putting my face in my hands. It was very effective.) Here are my lines, which I performed in my underpants at least 350 times over six years:

Jay: I can’t do it.

Craig (leader of the would-be working class strip group, feeling for Jay): Yeah, no problem.

Jay: I’m sorry. I can’t do it.

Craig: Yeah, it’s fine. (Awkward pause while Jay puts his clothes back on as hastily as he can – I sometimes got an extra laugh if I got tangled up, couldn’t find the sleeves etc.). Do you want a cup of tea?

Jay: No thanks, the kids are waiting outside. They shouldn’t see this.

That’s when the audience fell silent. Sometimes I could hear people in the front row gulp. I loved that moment: For me it was a tiny window into the bottomless sadness in the middle of the hilarity. After that, I hurried off stage-left, and the play went on.

Here comes Johnny singing oldies, goldies

This was in the spring of 2001, and playing Jay was one of the duties of my first job in Berlin. I was director’s assistant at the Tribüne, a theatre that is not only defunct but actually non-existent now, flattened and replaced with offices and a soup-and-salad bar. It was in a lovely Altbau on Otto-Suhr-Allee, one of the multi-laned boulevards off Ernst-Reuter-Platz, deep in West Berlin.

The plays we put on were almost all witty, easy-to-swallow, mid-20th century Anglo-American comedies, by Alan Ayckbourn or Woody Allen or Neil Simon. Any uncomfortable moments the scripts might have had were smoothed over by the translation and by directors who had little interest in unsettling our ageing audience, which shrank year by year. I didn’t get paid much, but it was a living, funded mainly by Berlin taxpayers, as part of a small cultural stipend designed to keep the diversity of Berlin’s private theatre scene alive.

It was a good first job to have, but between the shows and the bar with its warm Sekt and a featureless brown carpet that was fitted throughout the entire house, there was literally nothing cool about the Tribüne. In fact, at times it felt like the whole place and everyone in it was wilfully proud of having no cultural relevance. It was a place for tired people who wanted to do anything but confront the zeitgeist, especially watching some men make fools of themselves.

Shock me, put on your black leather

It was painful for young pseudo-intellectual me to admit at the time, but it looked like everything amazing was happening elsewhere – mainly at the Volksbühne, where Frank Castorf was putting on overwhelming destructions and reconstructions of classic novels, and actors weren’t so much performing shows as roaming free like children in their own chaotic built worlds.

German theatre is a difficult thing to love for most Anglo-Americans – it’s hard to get past the fact that you spend a lot of time watching naked people shouting – but for me, in the early 2000s, it was impossibly exhilarating. . Castorf turned revered plays that no English-speaking director would dare to touch into manic slapstick. I went to see his production of A Streetcar Named Desire three times. During the poker game scene, Stanley, played as a Polish dockworker in a Solidarność T-shirt by DDR acting legend Henry Hübchen, broke into a Britney Spears song and flipped playing cards into the audience. The Kowalskis’ apartment was a trailer on hydraulic legs that tilted up every now and then so the actors had to crawl up the floor, clinging desperately onto the edge of the sloping stage. One scene was interrupted while Stella Kowalski gave birth, filmed with a video camera by Stanley. Meanwhile, Williams’ original stage directions scrolled past irrelevantly on a red tickertape display high above, near the proscenium. Sometimes the actors stopped and read them aloud. You know the thrill that rushes through an audience when something goes wrong in a play? When an actor forgets their lines? Or an important prop gets dropped and smashes? Or an offended audience member interrupts the show and storms out? You feel the whole audience stir because they genuinely don’t know what’s about to happen. That feeling, that you’re dangling on the edge of chaos, was what Castorf’s shows were like, but not just momentarily – all the way through.

Don’t give me no lines (and keep your hands to yourself)

Castorf, who ran the Volksbühne from 1992 to 2017, had a precise antipathy to theatre as Anglo-audiences know it, which he expressed in 1996 like this: “Theatre often works according to a formula: You have characters act on stage who correspond to the people in the audience, and applause is guaranteed. In the foreground, society is being attacked, but in reality that society is celebrating itself inside an auditorium.” Castorf’s theatre was all about disrupting this act of masturbation (an image he used himself in a production of an 18th century German classic, much to the outrage and delight of critics). He once described the audience as his enemy, and he especially loved angering them in post-reunification Berlin, because, as he saw it, this was a city where “the German conflict was being fought confidently and honestly.” In the years after reunification this was a noisy building site of a city. The government hadn’t properly moved in, and was working out of provisional buildings or half-built offices. And Castorf loved it: “Things are humming, creaking, screeching, things are getting screwed together that don’t fit together at all. This city has never been a place of order anyway, but at the moment it’s providing important evidence that not every social space in Germany can be organized from a province in the Rhineland.” (Berliners loved to give Bonn a kicking any chance they got.)

The point of his Volksbühne was to do everything possible to prevent audiences escaping this. Audiences weren’t there to be entertained, they were there to be confronted with life in all its terrifying chaos. That five-hour version of The Master and Margarita I saw in between my Ladies Night shows was supposed to be exasperating, as was the eight-hour Faust production with which Castorf ended his tenure in 2017.

Turn and face the strange

Given that Castorf’s Volksbühne was a place for German contrarians who enjoyed annoying people, it makes a lot of sense that the Querdenker movement in Berlin first gathered on the steps of the Volksbühne in mid-2020.

By then, of course, Castorf’s stature was much reduced, his era over. He’d been dumped from the Volksbühne job by Berlin’s culture ministry three years previously: His first post-Volksbühne show was a much-panned seven-hour Les Misérables (the novel, not the musical) at the Berliner Ensemble in 2017. A year later he embarrassed himself with an interview in the Süddeutsche Zeitung saying women couldn’t direct plays as well as men, just like they couldn’t play football as well as men. He’d become just another boring patriarch-auteur complaining about his own increasing irrelevance.

His time was up, but his removal in 2017 caused an unwholesome row in Berlin’s cultural scene. The city government’s plan to turn the Volksbühne into a performance-space under the direction of Belgian curator Chris Dercon (of London’s Tate Gallery) looked to a lot of people like cultural gentrification: A much-loved institution was being uprooted to make way for some kind of mall of international art. Things turned ugly. Mean-spiritedly, Castorf and other regular Volksbühne directors refused to allow Dercon to put on their shows, which is pretty much normal practice during a transitional period. Protesters occupied the Volksbühne, human faeces were left outside Dercon’s interim office, and there was a petty row over the iconic wheel-with-legs sculpture on the front lawn. The Räuberrad (“Robber’s Wheel”) had become the Castorf Volksbühne’s logo, and so in May 2017, he and the sculptor who made it abducted it and shipped it off to Avignon, where Castorf was directing a show. It wasn’t clear if they had the right to do this, especially since it was owned by the Berlin state government. Eventually everyone calmed down and it was put back in 2018.

Good-bye everybody, I’ve got to go

Other old German theatre patriarchs rallied round Castorf like he was their dying monarch. The Berliner Ensemble’s artistic director Claus Peymann wrote an angry open letter in which he condemned the plan to turn the Volksbühne into what he called “an event shed,” as if it were going to be hired out to whatever show was in town.

This was unfair on Dercon, but it was an understandable reaction for anyone who could remember that this is exactly what happened to the great West Berlin theatres in the early 1990s. In those days, cash-strapped Berlin governments made a habit of saving money by shutting down cultural institutions like the Freie Volksbühne, (now the Haus der Berliner Festspiele on Schaperstraße), and the Schiller Theater, (shut down in 1993 and degraded into a temporary home for other theatres). Both of these beautiful auditoriums, once filled with their own permanent ensembles and unique artistic visions, are now just huge, state-run venues for hire. They’re no longer thriving cultural places woven into the city streets. When it comes to world-class cultural institutions, there’s a massive East-West imbalance now – while the east can boast riches like the Deutsches Theater, the Berliner Ensemble, the Maxim Gorki, and the Volksbühne, all the west has left is Thomas Ostermeier’s (admittedly world-class) Schaubühne.

The Volksbühne wasn’t gutted in the end. Dercon, literally sick of Berlin’s shit, put the whole mess behind him and moved to Paris. His successor, Klaus Dörr, managed three years but lost his job in 2021 after several women accused him of sleazy advances, sexist remarks, inappropriate intimacy, and bullying. Now the Volksbühne is run by René Pollesch, the playwright-director who put on much of his work during the mid-Castorf era in the 2000s as the **enfant terrible** leader of Volksbühne’s little-sister stage Prater. Many had seen him as a natural successor to Castorf, and perhaps Berlin could’ve saved itself a lot of trouble by appointing him four years earlier. So it goes.

Cos the players gonna play, play, play

No one came out of the saga of Castorf’s demise with their reputation clean, but theatre is a garden with many plants, and new venues have sprung up everywhere. And the last 20 years have shown there are different, less toxic ways of running a performance venue. The HAU theatres have sustained their own identity without the benefit of a fixed ensemble since the early 2000s, and there are new collaborative spaces like the contemporary dance-based Uferstudios in Gesundbrunnen that do without any artistic leadership altogether, and the Neuköllner Oper – so deeply rooted in the district it’s named after – is still going strong.

The Maxim Gorki Theater is probably the most exciting ensemble theatre in the city now, because it’s managed to catch something like the Volksbühne spirit without a suffocating patriarchal presence. It’s probably no coincidence that the Maxim Gorki also happens to be the only big theatre in Berlin run by a woman of colour: Shermin Langhoff, Turkish-born German, who took over in 2013 and turned the house into a multi-award-winning extravaganza of refugees and belly-dancing drag queens. Theatres thrive if their shows look as though they’ve grown out of the cities they live in, and the Maxim Gorki has made a point of mirroring multilingual, multi-ethnic Berlin. Castorf’s style – in which the actors were never just people dressed up pretending to be other people, but always themselves too – can still be felt in the documentary, confessional mode that has made big hits of the much-loved Yael Ronen shows such as Common Ground.

Not that everything’s perfect at the Maxim Gorki either.. Multi-ethnic and female-led or not, the system that underpins all traditional German ensemble theatres and their auteur productions is terminally hierarchical. Theatres are mini-dictatorships, or battleships, which makes them vulnerable to abuses of power.

In 2021, several Maxim Gorki workers accused Langhoff of bullying, including both verbal and physical abuse. A dramaturg accused Langhoff of unlawfully sacking her during her maternity leave. Despite over 40 complaints, Langhoff did not lose her job, though she was called in to explain herself to Culture Minister Klaus Lederer, (and agreed to take some coaching). And that led to him being accused of positive discrimination: Would he have sacked her if she’d been a man?

I will survive

Well anyway, losing things is part of life. My theatre career ended in 2008, when I almost had a nervous breakdown directing Sean O’Casey’s The End Of The Beginning at the Vagantenbühne (a theatre that is still thriving – it’s the cellar wedged under the Delphi Kino on Kantstraße). But sometimes I still get to fan the flames of my early passions. I translated a few plays by Sibylle Berg, including incendiary shows like Es sagt mir nichts, das sogenannte Draußen, (“The So-Called Outside Means Nothing To Me”) which have become big hits at the Maxim Gorki.

I enjoyed translating this a lot. It is a very free text. There are no character delineations, and it can be performed as a monologue, but Gorki’s brilliant show splits it into four parts: Four teenage women stomp around in baggy jumpers, dancing, describing their lives and recording a video for an unnamed man trapped in their cellar. Father? Abuser? We don’t really know, anyway he’s a captive audience, and the girls have a few things to tell him. It’s their turn now. This is definitely not Ladies Night.

My six years on and around a Berlin stage

From old outlaws to new icons: Ben Knight on his thwarted acting career, and the transformations in Berlin’s theatre life ever since he left it. (Published in Exberliner, July 2022)

(Photo: Thomas Grünholz)

You can leave your hat on

My character was called Jay, and he had four lines, the third of which I enjoyed saying, because it was the one that made the audience stop laughing. Up to that scene, the audience was usually already laughing a lot. This was my first appearance on a professional stage, and it was the biggest hit I would ever be involved in. Ladies Night was a version of the British movie The Full Monty, and in this production five German men played unemployed northern English steelworkers who stripped to groovy 1970s songs, in between scenes depicting male awkwardness, desperation, and despair, and finally triumph. The more clothes these men took off, the more they triumphed, until at the very end they took all their clothes off (police uniforms in this case) and the lights went out just at the moment you were about to see their cocks. Then the play was over. By then, our audiences had often become like the audiences at actual male strip shows. On some Friday nights, the 300-seat auditorium was filled with gales of female hilarity so relentless the actors could barely find a moment to get their lines out.

And in this howling din, towards the end of the slightly calmer first act, my character achieved a moment’s silence with his third line. Jay was auditioning to be a stripper, and he’d realized, as Serge Gainsbourg’s “Je t’aime” started, that he wasn’t cut out for this. When he did finally pull his trousers down, revealing a big pair of y-fronts (easy laugh there), he broke down in humiliation. (Not being an actor, I played this by putting my face in my hands. It was very effective.) Here are my lines, which I performed in my underpants at least 350 times over six years:

Jay: I can’t do it.

Craig (leader of the would-be working class strip group, feeling for Jay): Yeah, no problem.

Jay: I’m sorry. I can’t do it.

Craig: Yeah, it’s fine. (Awkward pause while Jay puts his clothes back on as hastily as he can – I sometimes got an extra laugh if I got tangled up, couldn’t find the sleeves etc.). Do you want a cup of tea?

Jay: No thanks, the kids are waiting outside. They shouldn’t see this.

That’s when the audience fell silent. Sometimes I could hear people in the front row gulp. I loved that moment: For me it was a tiny window into the bottomless sadness in the middle of the hilarity. After that, I hurried off stage-left, and the play went on.

Here comes Johnny singing oldies, goldies

This was in the spring of 2001, and playing Jay was one of the duties of my first job in Berlin. I was director’s assistant at the Tribüne, a theatre that is not only defunct but actually non-existent now, flattened and replaced with offices and a soup-and-salad bar. It was in a lovely Altbau on Otto-Suhr-Allee, one of the multi-laned boulevards off Ernst-Reuter-Platz, deep in West Berlin.

The plays we put on were almost all witty, easy-to-swallow, mid-20th century Anglo-American comedies, by Alan Ayckbourn or Woody Allen or Neil Simon. Any uncomfortable moments the scripts might have had were smoothed over by the translation and by directors who had little interest in unsettling our ageing audience, which shrank year by year. I didn’t get paid much, but it was a living, funded mainly by Berlin taxpayers, as part of a small cultural stipend designed to keep the diversity of Berlin’s private theatre scene alive.

It was a good first job to have, but between the shows and the bar with its warm Sekt and a featureless brown carpet that was fitted throughout the entire house, there was literally nothing cool about the Tribüne. In fact, at times it felt like the whole place and everyone in it was wilfully proud of having no cultural relevance. It was a place for tired people who wanted to do anything but confront the zeitgeist, especially watching some men make fools of themselves.

Shock me, put on your black leather

It was painful for young pseudo-intellectual me to admit at the time, but it looked like everything amazing was happening elsewhere – mainly at the Volksbühne, where Frank Castorf was putting on overwhelming destructions and reconstructions of classic novels, and actors weren’t so much performing shows as roaming free like children in their own chaotic built worlds.

German theatre is a difficult thing to love for most Anglo-Americans – it’s hard to get past the fact that you spend a lot of time watching naked people shouting – but for me, in the early 2000s, it was impossibly exhilarating. . Castorf turned revered plays that no English-speaking director would dare to touch into manic slapstick. I went to see his production of A Streetcar Named Desire three times. During the poker game scene, Stanley, played as a Polish dockworker in a Solidarność T-shirt by DDR acting legend Henry Hübchen, broke into a Britney Spears song and flipped playing cards into the audience. The Kowalskis’ apartment was a trailer on hydraulic legs that tilted up every now and then so the actors had to crawl up the floor, clinging desperately onto the edge of the sloping stage. One scene was interrupted while Stella Kowalski gave birth, filmed with a video camera by Stanley. Meanwhile, Williams’ original stage directions scrolled past irrelevantly on a red tickertape display high above, near the proscenium. Sometimes the actors stopped and read them aloud. You know the thrill that rushes through an audience when something goes wrong in a play? When an actor forgets their lines? Or an important prop gets dropped and smashes? Or an offended audience member interrupts the show and storms out? You feel the whole audience stir because they genuinely don’t know what’s about to happen. That feeling, that you’re dangling on the edge of chaos, was what Castorf’s shows were like, but not just momentarily – all the way through.

Don’t give me no lines (and keep your hands to yourself)

Castorf, who ran the Volksbühne from 1992 to 2017, had a precise antipathy to theatre as Anglo-audiences know it, which he expressed in 1996 like this: “Theatre often works according to a formula: You have characters act on stage who correspond to the people in the audience, and applause is guaranteed. In the foreground, society is being attacked, but in reality that society is celebrating itself inside an auditorium.” Castorf’s theatre was all about disrupting this act of masturbation (an image he used himself in a production of an 18th century German classic, much to the outrage and delight of critics). He once described the audience as his enemy, and he especially loved angering them in post-reunification Berlin, because, as he saw it, this was a city where “the German conflict was being fought confidently and honestly.” In the years after reunification this was a noisy building site of a city. The government hadn’t properly moved in, and was working out of provisional buildings or half-built offices. And Castorf loved it: “Things are humming, creaking, screeching, things are getting screwed together that don’t fit together at all. This city has never been a place of order anyway, but at the moment it’s providing important evidence that not every social space in Germany can be organized from a province in the Rhineland.” (Berliners loved to give Bonn a kicking any chance they got.)

The point of his Volksbühne was to do everything possible to prevent audiences escaping this. Audiences weren’t there to be entertained, they were there to be confronted with life in all its terrifying chaos. That five-hour version of The Master and Margarita I saw in between my Ladies Night shows was supposed to be exasperating, as was the eight-hour Faust production with which Castorf ended his tenure in 2017.

Turn and face the strange

Given that Castorf’s Volksbühne was a place for German contrarians who enjoyed annoying people, it makes a lot of sense that the Querdenker movement in Berlin first gathered on the steps of the Volksbühne in mid-2020.

By then, of course, Castorf’s stature was much reduced, his era over. He’d been dumped from the Volksbühne job by Berlin’s culture ministry three years previously: His first post-Volksbühne show was a much-panned seven-hour Les Misérables (the novel, not the musical) at the Berliner Ensemble in 2017. A year later he embarrassed himself with an interview in the Süddeutsche Zeitung saying women couldn’t direct plays as well as men, just like they couldn’t play football as well as men. He’d become just another boring patriarch-auteur complaining about his own increasing irrelevance.

His time was up, but his removal in 2017 caused an unwholesome row in Berlin’s cultural scene. The city government’s plan to turn the Volksbühne into a performance-space under the direction of Belgian curator Chris Dercon (of London’s Tate Gallery) looked to a lot of people like cultural gentrification: A much-loved institution was being uprooted to make way for some kind of mall of international art. Things turned ugly. Mean-spiritedly, Castorf and other regular Volksbühne directors refused to allow Dercon to put on their shows, which is pretty much normal practice during a transitional period. Protesters occupied the Volksbühne, human faeces were left outside Dercon’s interim office, and there was a petty row over the iconic wheel-with-legs sculpture on the front lawn. The Räuberrad (“Robber’s Wheel”) had become the Castorf Volksbühne’s logo, and so in May 2017, he and the sculptor who made it abducted it and shipped it off to Avignon, where Castorf was directing a show. It wasn’t clear if they had the right to do this, especially since it was owned by the Berlin state government. Eventually everyone calmed down and it was put back in 2018.

Good-bye everybody, I’ve got to go

Other old German theatre patriarchs rallied round Castorf like he was their dying monarch. The Berliner Ensemble’s artistic director Claus Peymann wrote an angry open letter in which he condemned the plan to turn the Volksbühne into what he called “an event shed,” as if it were going to be hired out to whatever show was in town.

This was unfair on Dercon, but it was an understandable reaction for anyone who could remember that this is exactly what happened to the great West Berlin theatres in the early 1990s. In those days, cash-strapped Berlin governments made a habit of saving money by shutting down cultural institutions like the Freie Volksbühne, (now the Haus der Berliner Festspiele on Schaperstraße), and the Schiller Theater, (shut down in 1993 and degraded into a temporary home for other theatres). Both of these beautiful auditoriums, once filled with their own permanent ensembles and unique artistic visions, are now just huge, state-run venues for hire. They’re no longer thriving cultural places woven into the city streets. When it comes to world-class cultural institutions, there’s a massive East-West imbalance now – while the east can boast riches like the Deutsches Theater, the Berliner Ensemble, the Maxim Gorki, and the Volksbühne, all the west has left is Thomas Ostermeier’s (admittedly world-class) Schaubühne.

The Volksbühne wasn’t gutted in the end. Dercon, literally sick of Berlin’s shit, put the whole mess behind him and moved to Paris. His successor, Klaus Dörr, managed three years but lost his job in 2021 after several women accused him of sleazy advances, sexist remarks, inappropriate intimacy, and bullying. Now the Volksbühne is run by René Pollesch, the playwright-director who put on much of his work during the mid-Castorf era in the 2000s as the **enfant terrible** leader of Volksbühne’s little-sister stage Prater. Many had seen him as a natural successor to Castorf, and perhaps Berlin could’ve saved itself a lot of trouble by appointing him four years earlier. So it goes.

Cos the players gonna play, play, play

No one came out of the saga of Castorf’s demise with their reputation clean, but theatre is a garden with many plants, and new venues have sprung up everywhere. And the last 20 years have shown there are different, less toxic ways of running a performance venue. The HAU theatres have sustained their own identity without the benefit of a fixed ensemble since the early 2000s, and there are new collaborative spaces like the contemporary dance-based Uferstudios in Gesundbrunnen that do without any artistic leadership altogether, and the Neuköllner Oper – so deeply rooted in the district it’s named after – is still going strong.

The Maxim Gorki Theater is probably the most exciting ensemble theatre in the city now, because it’s managed to catch something like the Volksbühne spirit without a suffocating patriarchal presence. It’s probably no coincidence that the Maxim Gorki also happens to be the only big theatre in Berlin run by a woman of colour: Shermin Langhoff, Turkish-born German, who took over in 2013 and turned the house into a multi-award-winning extravaganza of refugees and belly-dancing drag queens. Theatres thrive if their shows look as though they’ve grown out of the cities they live in, and the Maxim Gorki has made a point of mirroring multilingual, multi-ethnic Berlin. Castorf’s style – in which the actors were never just people dressed up pretending to be other people, but always themselves too – can still be felt in the documentary, confessional mode that has made big hits of the much-loved Yael Ronen shows such as Common Ground.

Not that everything’s perfect at the Maxim Gorki either.. Multi-ethnic and female-led or not, the system that underpins all traditional German ensemble theatres and their auteur productions is terminally hierarchical. Theatres are mini-dictatorships, or battleships, which makes them vulnerable to abuses of power.

In 2021, several Maxim Gorki workers accused Langhoff of bullying, including both verbal and physical abuse. A dramaturg accused Langhoff of unlawfully sacking her during her maternity leave. Despite over 40 complaints, Langhoff did not lose her job, though she was called in to explain herself to Culture Minister Klaus Lederer, (and agreed to take some coaching). And that led to him being accused of positive discrimination: Would he have sacked her if she’d been a man?

I will survive

Well anyway, losing things is part of life. My theatre career ended in 2008, when I almost had a nervous breakdown directing Sean O’Casey’s The End Of The Beginning at the Vagantenbühne (a theatre that is still thriving – it’s the cellar wedged under the Delphi Kino on Kantstraße). But sometimes I still get to fan the flames of my early passions. I translated a few plays by Sibylle Berg, including incendiary shows like Es sagt mir nichts, das sogenannte Draußen, (“The So-Called Outside Means Nothing To Me”) which have become big hits at the Maxim Gorki.

I enjoyed translating this a lot. It is a very free text. There are no character delineations, and it can be performed as a monologue, but Gorki’s brilliant show splits it into four parts: Four teenage women stomp around in baggy jumpers, dancing, describing their lives and recording a video for an unnamed man trapped in their cellar. Father? Abuser? We don’t really know, anyway he’s a captive audience, and the girls have a few things to tell him. It’s their turn now. This is definitely not Ladies Night.