The streets of Beirut are becoming ever more crowded as Lebanon is flooded with refugees from across the border in Syria. But the government still does not have a policy on what to do with them.

There is still a bus service running between Damascus and Beirut. In fact, if you know how to find them, there are still buses running from several places in Syria into Lebanon, though sometimes the service can be irregular. It’s advisable to call ahead to check that the driver is prepared to risk it today.

Mohammad last made the journey 18 months ago, and doesn’t want to repeat it any time soon. “When we heard shots, the bus driver would shout at everyone to duck down under the seat, and then he would speed through as fast as he can,” he said.

Just as nerve-shredding were the endless checkpoints, which drew out the bus journey to Beirut from his home town of Ar-Raqqah (about 100 miles east of Aleppo in northern Syria) from seven to 20 hours. “The government soldiers would get on and check to see who was on the bus,” he said. “If they took anyone, the people who were talking to them before would get really scared. People often get taken if they have the same name as someone the soldiers are looking for. Then sometimes they’re in prison for a month. That happens a lot.”

Dangerous roads

In the early part of the three-year conflict, Mohammad went through all this several times, travelling between his work as a mechanic and young family in Beirut and his extended family at home. He stopped going back when his home town was taken over by rebel forces – Ar-Raqqah is currently controlled by the jihadist group ISIS and is hit regularly by air strikes from Bashar al-Assad’s regime. His parents are still there, while he lives with his wife and two young children in one room plus kitchen in a camp in Dbayeh, just outside Beirut. The room is small but clean, contains a bed, a carpet, a chair, a sofa, a TV, and an electric heater, and it costs Mohammad $350 (250 euros) a month, which he earns by working as a mechanic for a small company nearby.

Leila, meanwhile, has to find $400 a month for her two rooms – shared by her extended family of nine, including her husband – “It’s misery,” he says coming in from his shift at a bottling warehouse nearby. He was working in Turkey when Leila abandoned their home in a village near Aleppo at 5am one morning in 2012. She says a neighbor knocked on the door to warn her that the rebels were going round forcing men to join up at gunpoint, so, fearing for her teenage son, she decided to leave there and then. “The situation was so dangerous that just walking a hundred meters from your house you didn’t know what would happen,” she said.

Making room

Lebanon, a country of five million, has had to absorb over a million refugees from Syria, but the government has no official policy or infrastructure in place to deal with them. That puts the Syrians in a freer but much more precarious predicament than in Jordan and Turkey, for instance, where they are funnelled into huge organized United Nations camps that they are often not allowed to leave.

The Syrians in Lebanon with money pay rent – often at inflated rates of $200 per month per room in the border regions up to $400 around Beirut. Sometimes clusters of families simply rent a field from a farmer and set up tents. The most destitute refugees simply end up on the streets of Beirut – young boys carrying boxes of rags and shoe polish, old women selling packets of paper tissues or chewing gum, mothers with babies in their arms begging.

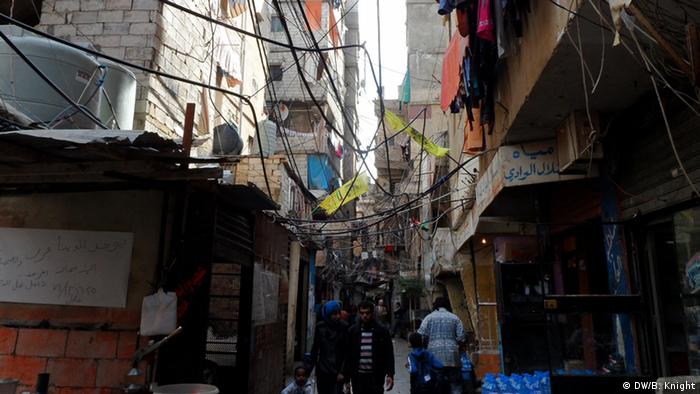

The fact that Syrians here have been left to themselves is partly down to Lebanon’s experience with the Palestinians forced across the border in 1948, and a repeat of those wearying decades when what were meant to be temporary camps gradually became heaving, cluttered improvised housing complexes like Beirut’s Sabra and Shatila. Here too, Syrians have now arrived to swell the numbers, and yet the Lebanese government is leery of providing more permanent space for a new exodus.

That has caused tension, not least because they are coming from a civil war zone. “With the refugees who are coming – some are with Assad, and some are against,” says Sylvia Haddad, director of the Lebanon branch of the Joint Christian Committee, an NGO that provides help for refugees across the Middle East. “But everyone is afraid of the new people who are coming to Syria – al Nusra, al Qaeda, I don’t know who these people are, but this is what we are afraid of now.”

The two sides of the civil war are a kind of taboo in the camps – the NGOs make it a policy not to ask, and the Syrians aren’t interested in mentioning it. Leila says that she never talks about politics with other refugees – she doesn’t even know if her neighbors are pro- or anti-Assad, she claims: “All I care about is to live in peace. We’re very tired of living here.”

Work and charity

In Beirut, Syrians who can work are accepting jobs sometimes for half the pay that the Lebanese take – and business-owners are not above exploiting the situation, which is increasing the tension. “They work well, and they work for much, much cheaper, and many are replacing the Lebanese people with the Syrians,” said Haddad. “Either you work or you steal – but in the end you have to eat.”

The JCC’s concentrates on providing social programs like kindergartens, sports, art, vocational classes, but when it can, it also helps refugees to pay their rent – though at the moment the budget will only stretch to subsidizing 12 families.

The JCC is about to start an afternoon program just for the new Syrian children in Sabra. “It will be a kind of psycho-social support, because they are suffering, these children,” said Haddad. “They have seen a lot of killing, they have lost a lot of their own family members. You don’t know what they have seen.”

“We used to have about 85 students in the Sabra center,” she added. “Because of all the Syrian demand we have taken 45 more children – we couldn’t take any more.”

Walid Damouny, a Palestinian refugee for his whole life, has been helping to modernize the electronics course. But even acquiring the skill to fix modern appliances does not mean that the Syrian children will have a good chance of finding work. “It depends – all the jobs have slumped right now because of the crisis in Syria. If the situation is quiet, Lebanon is a very good place to be, and if the situation is not, their chances will go down,” he said.